The Age Altertron Read online

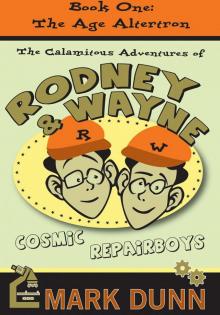

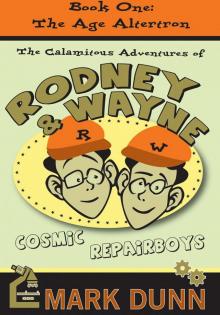

The Calamitous Adventures

of Wayne and Rodney

BOOK 1 - THE AGE ALTERTRON

Mark Dunn

ebook ISBN: 978-1-59692-823-7

M P Publishing Limited

12 Strathallan Crescent

Douglas

Isle of Man

IM2 4NR

via United Kingdom

Telephone: +44 (0)1624 618672

email: [email protected]

Originally published by:

MacAdam Cage

155 Sansome Street, Suite 550

San Francisco, CA 94104

www.MacAdamCage.com

Copyright © 2009 Mark Dunn

ALL RIGHTS RESERVED

Library of Congress Cataloging-in-Publication Data:

Dunn, Mark, 1956

Reluctant chrononauts / by Mark Dunn.

p. cm. —

(The calamitous adventures of Rodney and Wayne, the age altertron; bk. 1)

Summary: In a small, mid-twentieth century town that is secretly being used as a laboratory, thirteen-year-old twins Rodney and Wayne and their physicist friend, Professor Johnson, face a series of calamities including a time experiment that sends the boys from infancy to old age in just a few days.

ISBN 978-1-59692-345-4 (alk. paper)

[1. Time travel—Fiction. 2. Experiments—Fiction. 3. Scientists—Fiction. 4. Twins—Fiction. 5. Brothers—Fiction.] I. Title. PZ7.D92167Rel 2009 [Fic]—dc22

2009000977

Book design by Dorothy Carico Smith

Publisher’s Note: This is a work of fiction. Names, characters, places, and incidents either are the product of the author’s imagination or are used fictitiously. Any resemblance to actual events, locales, or persons, living or dead, is entirely coincidental.

MACADAM CAGE

This book is dedicated

to the memory of my twin brother Clay

who was a little bit of Rodney

and a whole lot of Wayne

The Age Altertron

A novel by Mark Dunn

Contents

Chapter 1

Chapter 2

Chapter 3

Chapter 4

Chapter 5

Chapter 6

Chapter 7

Chapter 8

Chapter 9

Chapter 10

Chapter 11

Chapter 12

Chapter 13

Acknowledgments

CHAPTER ONE

In which Rodney and Wayne wake one morning to discover that something isn’t quite right…again

Generally, it was Rodney who woke first, though, on occasion, his twin brother Wayne, who had a better nose for morning bacon than Rodney, would be off and down the stairs before Rodney knew it. But most often it was the younger of the two brothers who rose first and who knew first what kind of a day it was going to be.

Now, some days were fine and exactly what Rodney and Wayne expected them to be. Aunt Mildred would have breakfast waiting and a cheery “good morning” for both of her thirteen-year-old great-nephews. Sometimes there would be more than just bacon on the table. Rodney and Wayne would sit down to oatmeal with cinnamon or cinnamon buns or cinnamon toast. Aunt Mildred was quite fond of cinnamon and would sprinkle it on whatever she could, and her great-nephews Rodney and Wayne hardly ever complained (except when she put it on the scrambled eggs, because then the eggs tasted odd).

Aunt Mildred, you see, had begun craving cinnamon several months earlier when everything that was granular and sprinkleable in the town of Pitcherville was turned to cinnamon. This included most of the herbs and spices on Aunt Mildred’s kitchen herb and spice shelf, but also all the bath powder and tooth powder in town, and even all the sand in all the town sandboxes!

be the kind of thirteen-year-old boy you most wanted to be.

These were the days in which men wore brimmed hats to work and women wore hats of their own that sat flat and funny upon the head. These were the long-gone days in which the milkman brought not only milk but fresh creamy butter to your door, and the egg man brought eggs, and there were also people who came to your door to sell you brushes and vacuum cleaners or came to give you something they felt was important for you to read. These were the days in which television sets had rabbit-ear antennas that sat on the top and spindly antennas affixed to the roof, antennas that would pull three whole channels down from the sky, each channel giving you every kind of cowboy story you could ask for. And the only computer in town was the one to be found at Pitcherville College. It occupied nearly every inch of one whole room where it blinked and beeped and spat out punch cards.

Then there were the other mornings—the mornings when things were not right at all. Sometimes Rodney would wake, still drowsy with sleep, and wonder to himself, even before he had opened his eyes: “Will this be a normal day, or will it be one of the other kind?” And he only needed to open his eyes to learn the answer!

One Saturday morning in September, Rodney and Wayne woke to discover that everything in their town was the color of ripe peaches. Wayne pulled back the covers from his peach-colored bed and slapped his bare feet upon the peach-colored rug that covered the peach-colored floor of the bedroom he shared with his brother. He went to the window and looked out and could hardly tell one thing from another, because the lawn, the trees, the street upon which the boys lived—everything that he could see from his window— was the same color.

Peach.

“Hey, get a load of this!” Wayne exclaimed to Rodney, as he waved him over to the window. (Rodney could hardly see Wayne’s waving arm, since it was the same color as the wall.) “It looks like Mr. Lipe’s car just crashed into Mr. Edwards’ car, and lookit over there.”

“Where?”

“Where I’m pointing. Squint your eyes a little. See Mrs. Carter and Mrs.Wyatt? They’re both sitting on the sidewalk rubbing their heads. It looks like they just bumped their heads together.”

The boys stood for a moment longer at the window, whistling in wonderment, before putting on their weekend clothes and going down to join their aunt in the kitchen.

“It’s terrible, just terrible, boys!” said Aunt Mildred in a fretful tone. “Everything is the color of peaches—everything except for peaches themselves. For some reason they’re now blue.”

Wayne picked up one of the blue peaches from the fruit bowl on the table. “I wonder if they still taste like peaches.”

“Well, there’s no time to find out. You must go to Professor Johnson’s house this instant and ask him how long we’re going to have to endure this. It’s a terrible inconvenience—worse than all the others that have befallen this unfortunate town. While you are speaking to him, ask him why we deserve this—why should we always be put to such trouble? I would take you boys by the hand and run away from this place as fast as our six legs could carry us were it not for that dastardly force field that prevents any of us from leaving.”

Aunt Mildred sat down in her peach-colored chair and fanned herself with a peach-colored Ladies’ Home Journal that was otherwise useless to her now.

Wayne went to his aunt and kissed her on the forehead. He stepped back and stood, posed just the way his favorite comic book hero, Mighty Mike, stood, with one hand upon his hip and the other raised in the air as if he were about to give a speech. Standing in this silly way, Wayne proclaimed, “Have no fear, kind lady! The evil that lives behind this…this…”

“Peachiness,” said Rodney, trying to be helpful.

“Peachiness—it will not stand! And now, my faithful companion Rodney, let us fly to the laboratory of good Professor Johnson.”

Rodney hated the role of the faithful companion to Mighty Mike. The superhero’s tr

ue companion, Beaver Boy, was generally ignored by Mighty Mike except when he needed a dam built.

On their way to Professor Johnson’s home laboratory, the boys were careful not to collide with any trees or mailboxes or lampposts. “Aunt Mildred is wrong,” said Rodney. “This is not the worst thing that has ever happened to the town of Pitcherville. I can think of a dozen other calamities that were much worse than this one.”

Then the boys began to list all of the strange things that had happened to Pitcherville in the last eleven months. Rodney and Wayne remembered the day that the Troubles had started; it was the same day their father disappeared. It was also the day that Professor Johnson, not knowing about Rodney and Wayne’s father, had come to deliver his own sad news: his laboratory assistant Ivan and two professors at his college had vanished without a clue. The Professor was going from house to house helping the police with their search. He was also curious to know if his neighbors were having the same sort of personal trouble that he was having.

The personal trouble was this: every time the Professor opened his mouth to speak, all that came out was a series of numbers. And when the Professor looked all about him, he saw nothing but numbers in all the places where words usually appeared: throughout his daily newspaper, for example, or inside his copies of Science Todaymagazine. All the words on the street signs and store signs had also been replaced by numbers. Even the town billboards had only numbers on them. For example, the Plash Detergent billboard didn’t sell Plash Detergent anymore. It sold a product called “86-42,” although it had the same picture on it as before: a happy woman holding up clothes that gleamed with cleanness.

In answer to Professor Johnson’s numerical inquiry, Rodney shrugged and said, “Fifty-seven.”

And this was why it took two full days for Professor Johnson to learn that Rodney and Wayne’s father, Mitch McCall, had also been among those townspeople who were later to be remembered as “The Vanished.” Until the Professor succeeded in completing his Alpha-Numerical Transferal Machine and activating it to correct this problem of words being turned into numbers, conversations between the boys and their new professorial friend generally went something like this:

“Five-hundred-fifty-four—four-hundred-and-nine—three— twenty-two,” said Rodney in a calm but worrisome voice.

“Sixty-six-thousand-and-one,” said Wayne, nodding eagerly.

“Thirty-three—six-hundred-and-seventy-two,”replied Professor Johnson with a perplexed look (because he had no clue what it was that the boys had just said).

“That Pandenumberum was far worse than this peach thing,” recalled Rodney.

Wayne nodded. “And the Hubbubblia was even worse that that! The town was so full of bubbles that you could hardly move without squeaking and feeling cleaner than a person generally cares to feel.”

“Remember last spring when everybody’s arms turned into flippers?” asked Rodney.

“The Flip Out? Boy do I!” replied Wayne. “It took me almost an hour just to put on my pajamas! And we couldn’t watch any of our favorite television programs because nobody could turn the knob that switches the set on.”

“And that lasted a whole week!”

“Because that was before we started helping Professor Johnson. Notice that he does a much faster job fixing these problems when we can lend him a hand.”

“Or a flipper,” added Rodney, with a grin.

CHAPTER TWO

In which the Professor and Rodney and Wayne work together to save the town of Pitcherville (yet again) while losing a few friends among its canine population

hen the boys reached the Professor’s house they found the tall, thin man (who looked a little like Abraham Lincoln, but without the beard and the stovepipe hat) diligently at work in his laboratory in the back. The laboratory had its own door, which was almost never locked. There was a good reason for this; when the professor was busy with one of his new machines, he was hardly ever aware of the sounds around him, including knocks—even very loud ones. So, Rodney and Wayne had gotten into the habit of letting themselves in and waiting for the Professor to notice their presence with a nod and a smile and a very long description of what he had just been doing. Sometimes his explanation made perfect sense. For example, he would say, “Boys, I am putting a metal plate here so all this delicate circuitry won’t be exposed.” At other times what he said made no sense at all. For example: “Boys, the master diode has a flux of seven when I require at least an eight-point-two.”

Rodney and Wayne and the Professor had become very good friends since the day he had come to their door eleven months earlier. With their dad now gone, the twins looked up to him as sons would look up to their father. The Professor was happy to have the boys for assistants and also to have them as his friends. The life of a college physics professor—a life spent teaching and reading and working on contraptions in his home lab that would save a town from all manner of continuing calamities—was a fairly lonely life. Rodney and Wayne made good company for the solitary professor, even when they weren’t handing him a wrench or a screwdriver.

“Hello, boys,” said the Professor. “Your timing could not have been better. How do you like my Peach Pigment Evanescizer? I have just this minute completed its construction.”

“Well,” said Rodney, looking over the machine, “it looks very much like your Lemon Pigment Evanescizer.”

“An astute observation,” said the Professor, wiping his dirty hands on his lab coat. “It works very much like the Evanescizer we used to remove all the lemon color from the town two months ago.” The Professor took a bite from the sandwich that his housekeeper and cook Mrs. Ferrell had left for him before she went off to the grocery store. It was the Professor’s favorite sandwich. In fact, it was the only kind of sandwich he would eat: sardines and Swiss cheese. Rodney and Wayne had tried it themselves once and secretly called it “Professor Johnson’s ‘Yuck’ sandwich.”

“It sounds to me,” said Rodney, running his hand along the smooth aluminum housing of the machine, “that the peach color will be just as easy to remove as the lemon color was.”

“One would think so,” said the Professor, extracting a small peach-colored sardine from his sandwich to give to his fish-loving half-Persian/half Siamese cat Gizmo. Gizmo sniffed the small fish (because it didn’t look familiar to her). Then, satisfied that it was fishy in nature, she took it directly from her master’s hand and gobbled it down. Then she carried her very furry body over to her sleeping pillow and began to clean the fish oil from her mouth with a spitty paw.

“But here is the thing,” the Professor went on. “The color known as lemon is very similar to its parent color yellow. There is very little variation in hue at all. And what do we know about the coloryellow?”

“That it is a primary color?” asked Rodney.

“You’re exactly right. Whereas peach is a combination of several different primary and secondary colors. It’s a much more complicated sort of color to dispense with. So, my frequency generator will have to be tuned to a much higher pitch. And do we know what happens when a frequency generator is tuned to a higher pitch?”

Rodney shrugged. Wayne shrugged.

“Think about it, boys. It has something to do with dogs. It has something to do with every dog in the town of Pitcherville.”

“I think it must be a frequency that only dogs can hear!” said Wayne proudly.

“But more than that—”

The boys thought about this for a moment but could not arrive at the answer.

“Dogs may be the only creatures to hear the high frequency, but will they like it?” hinted the Professor.

Wayne shook his head in large part because Professor Johnson was shaking his head to steer him to the correct answer.

“No siree, boys, they won’t take to it at all. We’ll have quite a bit of yelping and yowling to deal with until all the pigment has been shaken loose from this town, and you can bet that Officer Wall from the Pitcherville Police Department’s

Loud Noises Unit will be at my door lickety split to write me a summons. Just you wait.”

“And there’s no other way to do what we have to do?” asked Rodney.

“I’m afraid there isn’t. It is the price that we must pay for science. Now, I have a very important job for the both of you. Here is a screwdriver for you, Rodney, and here is one for you, Wayne, and here are some canine earmuffs I have made for my little terrier Tesla. You will be custodian of those, Wayne. Now…when Tesla comes running in here howling and yowling you must catch him and put these on his ears, for it will be loudest here inside my house and I do not wish for him to be made too uncomfortable.”

Wayne nodded. He held a screwdriver in one hand and the canine earmuffs in the other. “But Professor,” said Wayne, “what are the screwdrivers for?”

“Perhaps your brother Rodney knows?”

Rodney thought for a moment while scratching his forehead with the business end of his screwdriver. Then his face brightened. “Well, I remember that the other machine—the one you built this one from…”

“The Lemon Pigment Evanescizer. Yes, go on…”

“Well, I remember that once it started really going, it began to rattle, and before we finished, it was rattling quite a lot, and some of the screws that were holding it together almost shook themselves out of their grooves. I suppose, Professor, that this one rattles even more than that one did.”

“Your supposition is correct.”

“So we’ll have to work even harder to keep these screws from coming out.”

“And to keep the Evanescizer from totally dismantling itself! Rodney, my boy, that was a crackerjack observation—quite astute, right on the money!”

Wayne’s heart sank. He had been excited and eager to do his part to save the town of Pitcherville from its latest disaster, but now the happy feeling was gone. He bowed his head and looked down at the floor so that Rodney and the Professor couldn’t see in his face how badly he felt.

American Decameron

American Decameron Ella Minnow Pea

Ella Minnow Pea We Five

We Five IBID: A Life

IBID: A Life The Calamitous Adventures of Rodney and Wayne, Cosmic Repairboys: The Age Altertron

The Calamitous Adventures of Rodney and Wayne, Cosmic Repairboys: The Age Altertron The Age Altertron

The Age Altertron IBID

IBID